President Trump was recently quoted as saying: “the heat, generally speaking, kills this kind of virus,” in reference to the impending warmer spring weather calming the spread of novel coronavirus (COVID-19). While the ambient heat of the warmest spring day may not be enough to kill the virus, according to leading epidemiologist Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, it may help to stymie its transmissibility. To quote Dr. Fauci, “It’s not unreasonable to make the assumption [that cases will die down come spring],” as he told NPR, and repeated on numerous news outlets.

The assumption that Dr. Fauci is referring to is a popular theory in epidemiological circles, and there is data to support the claim, though the underlying biomedical science explaining the phenomenon is somewhat dubious. Elizabeth McGraw who directs the Center for Infectious Disease Dynamics at Pennsylvania State University explains it as such: The warmer more humid, heavier air makes infectious droplets less transmissible, and the cold, dry air of the winter, facilitates the spread of the virus’ infectious droplets.

The main issue with this theory is that in the Southern Hemisphere, infectious diseases like influenza peak during the rainy seasons, which are of course, humid and rainy. Transmissibility cannot thus be a function of cold and dry air.

How then does Tibetan Medical Science explain the seasonality of infectious diseases like influenza or novel coronavirus?

Tibetan Medical Science purports that autumn is when infectious diseases are most transmissible due to the season’s hot and sharp cosmic energies. This is consistent with epidemiological data showing increased cases of influenza beginning late September, in the Northern Hemisphere, and at the beginning of March in the Southern Hemisphere.

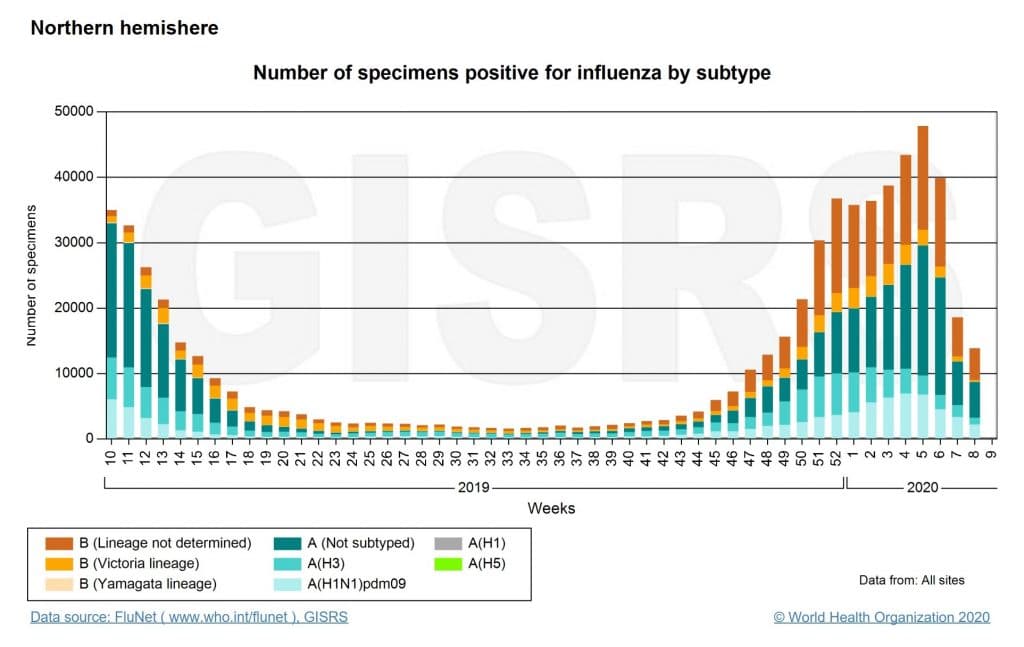

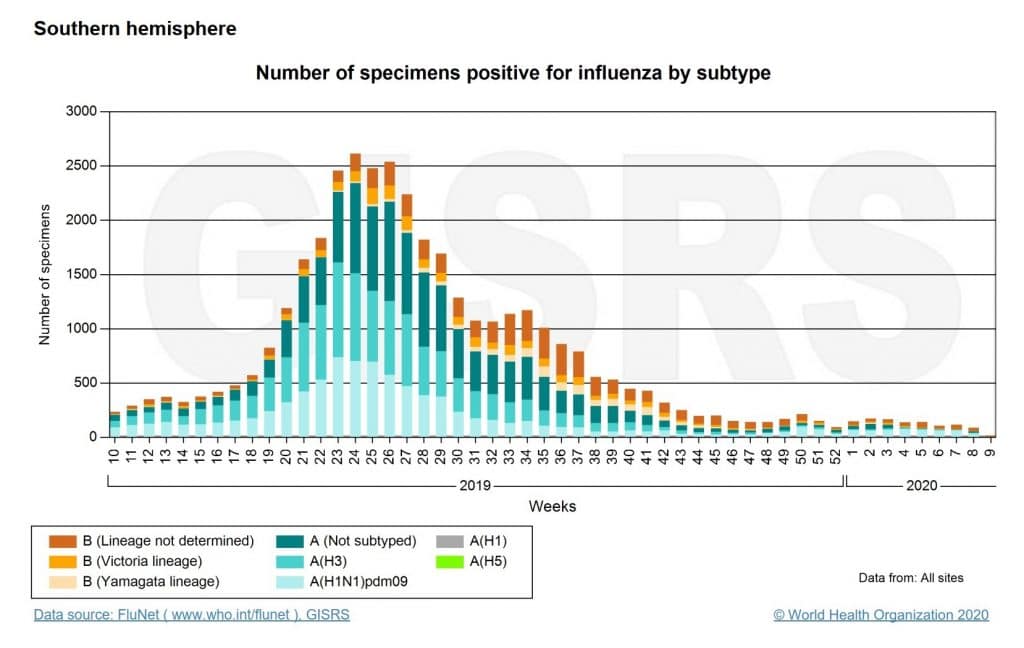

The graphs above were pulled from the World Health Organization’s Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS). The Northern Hemisphere chart shows an upward trending inflection point in the number of flu cases around the 40th week of the year, coinciding with the beginning of autumn (September 23rd, 2019); similarly, the Southern Hemisphere chart shows a stark uptick in cases around the 15th week of the year, also the start of autumn (March 20th, 2019).

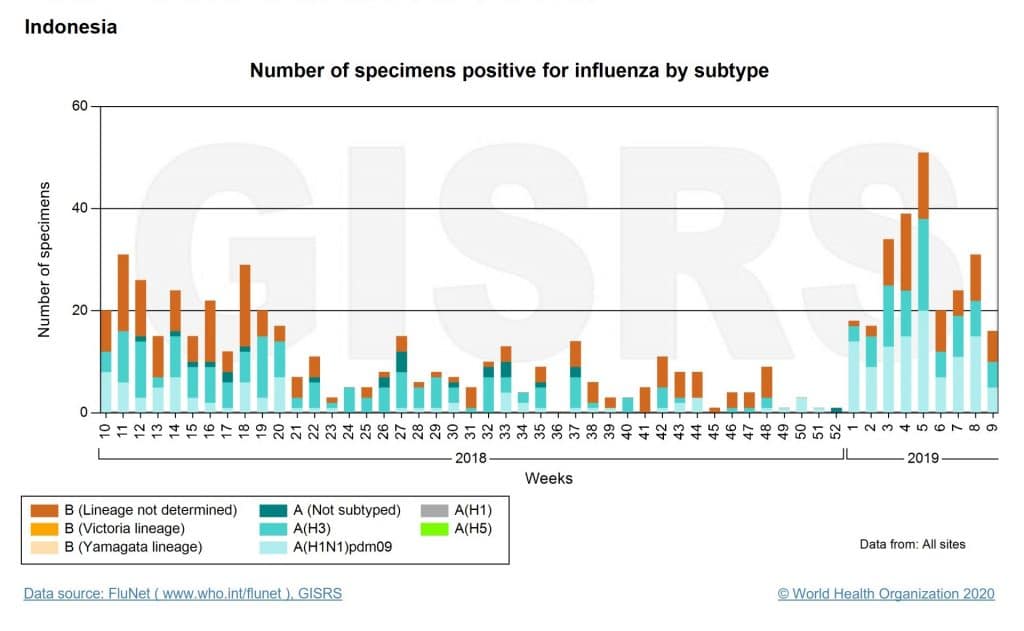

In tropical regions that lie on the equator and don’t have four distinct seasons, like Indonesia, the largest numbers of flu cases can be seen during the very wet and humid monsoon season of November to March (weeks 44-12). This again dispels the seasonality theory requiring cold air for transmission.

From the above two charts there are consistent data illustrating the seasonality of influenza which, from the perspective of Tibetan medical science, can be applied to COVID-19, as both are hot-natured infectious diseases. In the Northern Hemisphere we see a decline of flu cases after week #5, and in the the Southern Hemisphere, it’s week #26. Both of these weeks occur in the winter months. We can thus infer from this and other similar data subsets available from the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control that influenza cases begin to rise in autumn, peak into the winter months, and subside thereafter, reaching a minimum in the summer season. In Tibetan Medical Science, the spring season is the energetic opposite of the autumn; it then theoretically holds that the pervading cool and blunt energies of the spring will not encourage transmission of communicable diseases.

Therefore, according to Tibetan medical science, the coming spring season in the Northern Hemisphere should indeed help to reduce the transmission of COVID-19, but the Southern Hemisphere should see a spike in cases.